Suffragettes and Prison Conditions in Ireland

An exhibition of documents from the archives of the General Prisons Board documenting the prison conditions of women sentenced to incarceration in Ireland as part of their campaign for women’s suffrage, 1912-1914.

December 2018 marked the 100th anniversary of the first general election held following the enactment of the Representation of the People Act, 1918, which granted limited suffrage to women over 30 years of age and universal suffrage to men over 21 years of age. The Act followed a long campaign by women and working class men for recognition of their contribution to society and their right to participate and vote in elections. The expansion of cities throughout the United Kingdom and the move away from traditional rural hierarchies, coupled with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, and the Easter Rising in Ireland in 1916, had resulted in changes in attitude by many sections of society. Men who had fought in the trenches were no longer willing to accept a limited place in a society governed by the landed elite, and women who had waged a campaign for suffrage in the years before the outbreak of war were intent on reigniting their struggle.

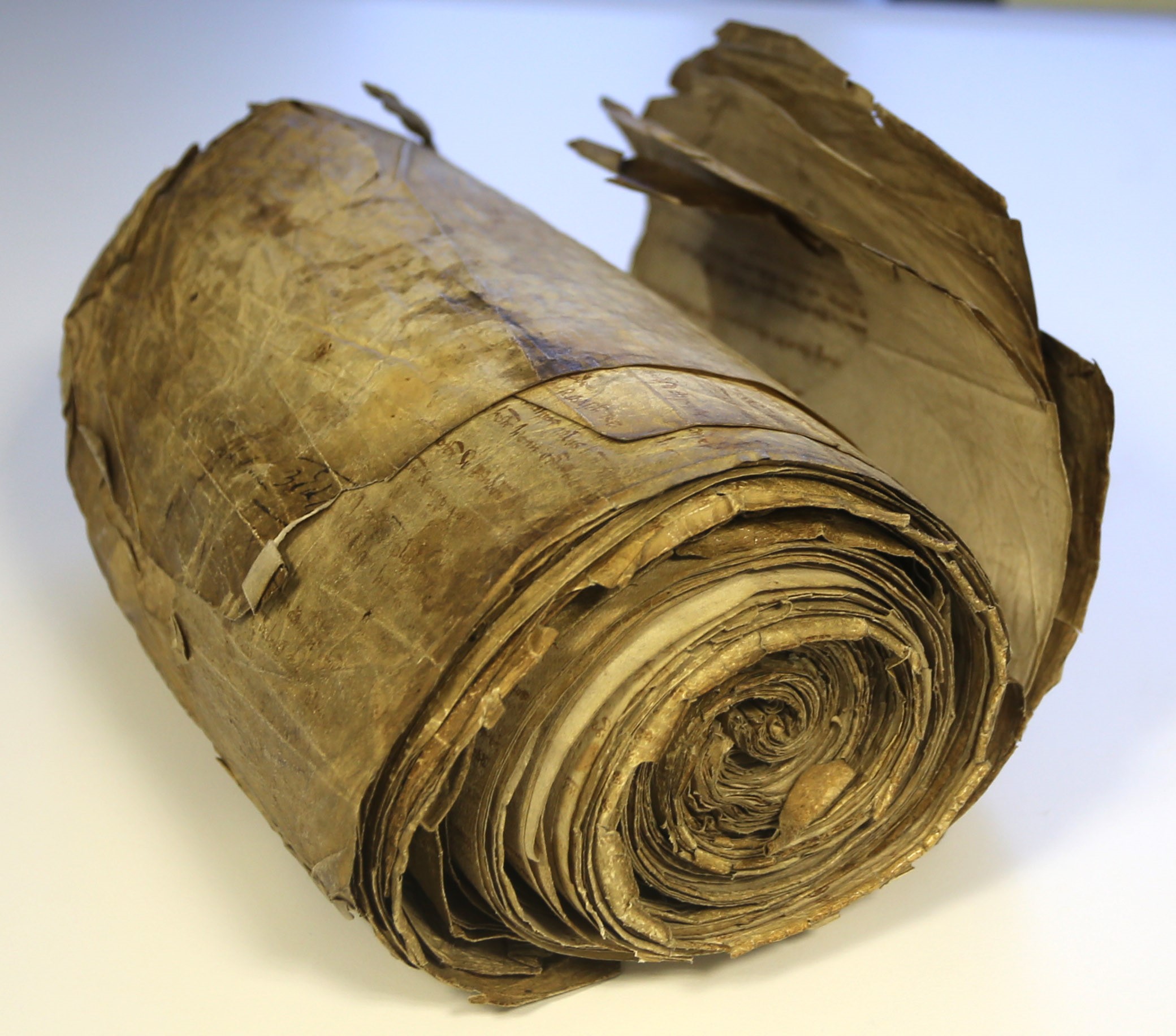

The National Archives holds a series of prisoner files created by the General Prisons Board (GPB) between 1912 and 1914, which detail the imprisonment of women campaigning for their right to vote. In the 1911 census, a number of members of the campaign attempted to subvert the process by either absenting themselves from home in an effort to avoid the enumerator calling to their door, or in the case of women like Mabel Small, consciously objecting to the process by refusing to provide any details to the enumerator. The 1911 census return for Small, who lived in Belfast, was completed by the enumerator, who noted on the form that Small and her housemate considered themselves ‘militant suffragists’ (NAI, 1911/Census/Antrim/90/29). Small, like many of her fellow suffragettes, contended that as society had refused to count them as individuals who were allowed to actively participate in the political process they would no longer facilitate participation in official undertakings such as the census. The GPB Suffragette series (NAI, GPB/SFRG/1) contains a file on Mabel Small, who was later convicted in the Belfast assizes of breaking panes of glass.

In a report of her trial in Belfast, Dorothy Evans, who was charged with having material for making explosives, challenged her right to a fair trial by a jury of her peers. The jury, as was the case at the time, was made up entirely of men. In addressing the charge against the court, the presiding judge Mr Justice Dodd stated ‘You are a lady, and whatever else has happened in your life remember that. You are now under courtesy, the courtesy of your sex, apart from anything else, obliged to listen’ (NAI, GBP/SFRG/1/13).

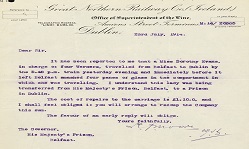

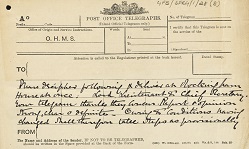

Evans’ trial was postponed and she was remanded in custody to appear at the next sitting of the Belfast assizes. During her transfer to Tullamore Prison on 22 July 1914, she smashed a number of window panes on the train and threw a postcard she had written on to the platform at Geashill, King’s County [County Offaly], where it was picked up by the Station Master and given to a postman. Once in Tullamore, she began a hunger strike and was released on the 25 July 1914 following a recommendation by the Medical Officer JM Prior Kennedy who stated in his report to the governor that ‘…her condition is such that further abstention from food and fluids will endanger her life’[1].

The campaign for women’s suffrage was not a cohesive body and consisted of organisations, some of whom believed in peaceful protest and others, such as the Irish Women’s Franchise League, who felt they should follow a similar campaign of violent protest and resistance as had been undertaken in England. In correspondence, dated 21 February 1913, from J Boland, governor of Tullamore Prison, he states ‘This country is fairly free from the militant tactics of the suffragettes compared with their doings in England & Scotland’[2].

Many of the women involved in the campaign in Ireland had also been imprisoned in England. These included well-known campaigners such as Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Margaret Palmer, who had both been imprisoned in Holloway. Despite such close links, it was not until 1912 that campaigners in Ireland began to undertake a campaign of active violent resistance when a campaign of window breaking began. The leaders of the movement, including Sheehy-Skeffington and Palmer, were arrested and brought before the Petty Sessions, the precursor to the modern District Court, where they were found guilty and fined. Upon refusing to pay these fines, suffragettes were imprisoned.

The campaign was initially concentrated in Dublin and prisoners were sent to Mountjoy Prison, but in 1913 the campaign escalated in its ferocity and spread to Belfast. The authorities were anxious to control the situation and to avoid any adverse publicity, particularly in view of the fact that many of the campaigners were members of the wealthy, educated middle classes who moved in the same social circles as civil servants and those in government. The suffragette files contain multiple letters and petitions from members of the public. Although many of these individuals did not agree with the tactics of the militant movement, they did, in most cases, support the campaign for women’s suffrage and believed the authorities had a duty of care to these women. Following a number of protests held outside Mountjoy Prison, a decision was taken in 1913 to send all suffragette prisoners to Tullamore, King’s County [County Offaly] where any attempt to organise would be much more difficult and less likely to spread to the general prison population.

Almost immediately after they were sent to prison, the suffragettes demanded to be acknowledged as political prisoners. In memoranda to the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Aberdeen, they outlined their reasons for resorting to breaking the law and their decision to engage in a campaign of active resistance. For the authorities, this was a new and unique situation. The correspondence between the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle and the GPB is full of uncertainty as to how such women should be dealt with. The authorities consistently refused to acknowledge any political motivation referring to prison rules and an inability to sanction such a move, while at the same time attempting to appease the women in almost all of their demands for special treatment. In a memorandum, dated 1908, it was stated that no political prisoners had been imprisoned in Ireland since 1870. Although they had broken the law nobody, including the suffragettes themselves, viewed these women as common criminals. They were not held in the same areas or conditions as criminal convicts and were offered diets and concessions that criminal convicts were not entitled to or only received after lengthy periods in prison with good behaviour.

In order to bring attention to their demands, suffragette prisoners organised a coordinated campaign of hunger strikes. The suffragette prison population in Ireland remained very low but they used their imprisonment very effectively, and extensive coverage was given to the campaign in newspapers who monitored developments closely. In the United Kingdom prison authorities had used force feeding to undermine this campaign. They contended that force feeding was a means of maintaining prison discipline. In Ireland, there was reluctance at a political level to follow suit. This is demonstrated in correspondence between the GPB, the prison governors and the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle who were anxious that the situation was contained and did not result in the death of any suffragette prisoners while in custody, or become a major propaganda victory for the suffragette movement.

The GPB files demonstrate the protracted debate by the authorities as to how they would deal with the issue of force feeding and refusal of food by suffragette prisoners. Eventually, a decision was taken by Lord Aberdeen not to engage in force feeding of Irish prisoners. Instead, the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act, also known as the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act, 1913 was used against hunger-striking suffragettes to undermine their reserve and to prevent any deaths in custody. In the majority of cases, prisoners on hunger strike were released into the care of family or friends on a temporary basis to receive medical attention. Once the individual’s strength returned they could be rearrested and sent back to prison. In reality, this did not happen but was used as a constant threat to undermine those campaigning through active resistance.

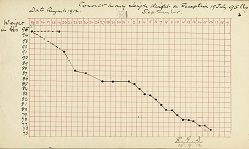

Only two female suffragette prisoners imprisoned in Ireland were force fed. Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans were veterans of the English suffragette campaign and had travelled to Ireland to protest against Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, who was in Dublin in July 1912 to address a Home Rule meeting. Leigh and Evans were imprisoned for five years hard labour for throwing an axe at Asquith and for attempting to set fire to the Theatre Royal, where he was due to speak the following day. In the opinion of the authorities in Dublin Castle and the GPB, their sentence to hard labour prevented any opportunity for leniency, which had been granted to their fellow Irish suffragettes. This included any special treatment or subjection to force feeding. Whereas Irish female suffragettes on hunger strike were released once their health began to deteriorate, a decision was taken to force feed both Leigh and Evans. This took place in Mountjoy Prison over the course of a number of weeks in August and September 1912 and was overseen by the prison Medical Officer RG Dowdall. Dowdall maintained a close watch on the prisoners and documented their deterioration and weight loss over the duration of their hunger strike and force feeding. The details of the procedure, the impact on the women’s bodies and psychological frame of mind, as well as their resistance to being artificially fed by nasal and stomach tube is fully documented in his reports, which are included in the files.

Dowdall was requested to submit a report each day to the GPB, which was then sent on to Dublin Castle in order to keep the Chief Secretary and Lord Lieutenant informed of any developments. It is not possible to determine conclusively from the files why such a course of action was taken for these women only, but in the court’s ruling the presiding judge referred to the severity of the sentence as a deterrent to other suffragettes and it is possible that the force feeding of the women was used as a punishment and as an attempt to prevent any escalation of the level of resistance in Ireland. Mary Leigh had been subjected to force feeding while in prison in Birmingham. In a report sent to the prison authorities in Ireland, Ernest Hasler Helby, the former medical office in Birmingham Prison, outlined the treatment that she had been subjected to.

He also noted that Leigh was from a working class background and in his opinion was being used by the suffragette campaign, and in particular by members of the higher classes, to further their ends. He states ‘Leigh was one of the most difficult cases we have had to deal with, she is a most obstinate self-willed woman liable at times to outbreaks of violence at other times to be sullen & morose. She was not of the same social position to which many of her companions belonged and owing to the extremes to which she was willing to go, in what they term, forwarding their cause, she had been made much of by the leaders, which had flattered her vanity making her reckless of danger to her own health or even of her life’ (NAI, GPB/SFRG/1/29/Part II).

The treatment of Leigh and Evans contrasts with Irish suffragettes imprisoned in Tullamore. In a memorandum to the GPB, dated 20 October 1912, J Boland, governor of Tullamore Prison, outlines the preparations that have been made to accommodate the proposed transfer of suffragette prisoners from Mountjoy Prison. This includes their segregation away from the general prison population in rooms in the male hospital wing and special furnishings to make the rooms more comfortable. An ordnance survey map of the prison is included as part of the proposal (NAI, GPB/SFRG/1/22). These prisoners were allowed to wear their own clothes and to associate with each other. They were also permitted special visits in a separate area away from the general prison population and were allowed the services of an ordinary prisoner to clean their rooms.

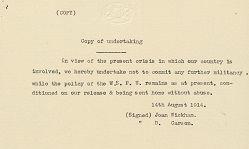

Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, the authorities called on the militant suffragettes to cease their campaign of resistance in order to support the war effort. On 10 August 1914, the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna[3], ordered an amnesty releasing all suffragette prisoners who agreed not to commit any further crimes or outrages. In his speech to the House of Commons he stated ‘His Majesty is confident that the prisoners of both classes will respond to the feelings of their countrymen and countrywomen in this time of emergency, and that they may be trusted not to stain the causes they have at heart by any further crime or disorder’[4].

In August 1914, Joan Wickham and D Carson were on hunger strike in Belfast Prison and were refusing to leave despite the recommendation by the Medical Officer, J Stewart, that they be released due to their deteriorating health. They had been rearrested for breaking windows following their trial for setting fire to Lisburn Cathedral along with Gladys Evans and Lillian Metge. After a visit from their solicitor Mr [George] McCracken, who had been in correspondence with the Under Secretary in Dublin Castle about the matter, both Wickham and Carson signed a declaration agreeing to desist from further violent conduct ‘in view of the present crisis in which our country is involved’ (NAI, GPB/SFRG/1/16). They were both released by order of the Lord Lieutenant later that evening. The militant suffragette movement ceased and turned their focus to the war effort and the expansion of women in the workforce.

The Representation of the People Act, which became law in February 1918, granted partial suffrage to women and the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, 1918 allowed women to stand as members of parliament for the first time. Voting rights were granted to those over 30 years of age who were registered property owners or married to a registered property occupier with a rateable value of £5 or more. Universal suffrage for women over 21 years of age, regardless of property, was not introduced in Ireland until 1922 following the establishment of the Irish Free State, and the United Kingdom until 1928.

[1]NAI, GPB/SFRG/1/13.

[2] NAI, GPB/SFRG/1/31.

[3] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/people/mr-reginald-mckenna/index.html (accessed, 10 December 2018).

[4] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1914/aug/10/release-of-prisoners#S5CV0065P0_19140810_HOC_180 (accessed, 10 December 2018).

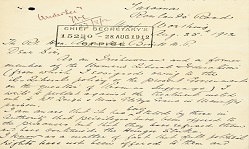

Urgent telegram to the Chief Secretary in Rockingham House, County Roscommon, from the Lord Lieutenant concerning the deterioration of Gladys Evans.