Behind the Scenes

Behind the Scenes: ‘We’ve seen the Pillars tumble’ – The fall of James Pillar

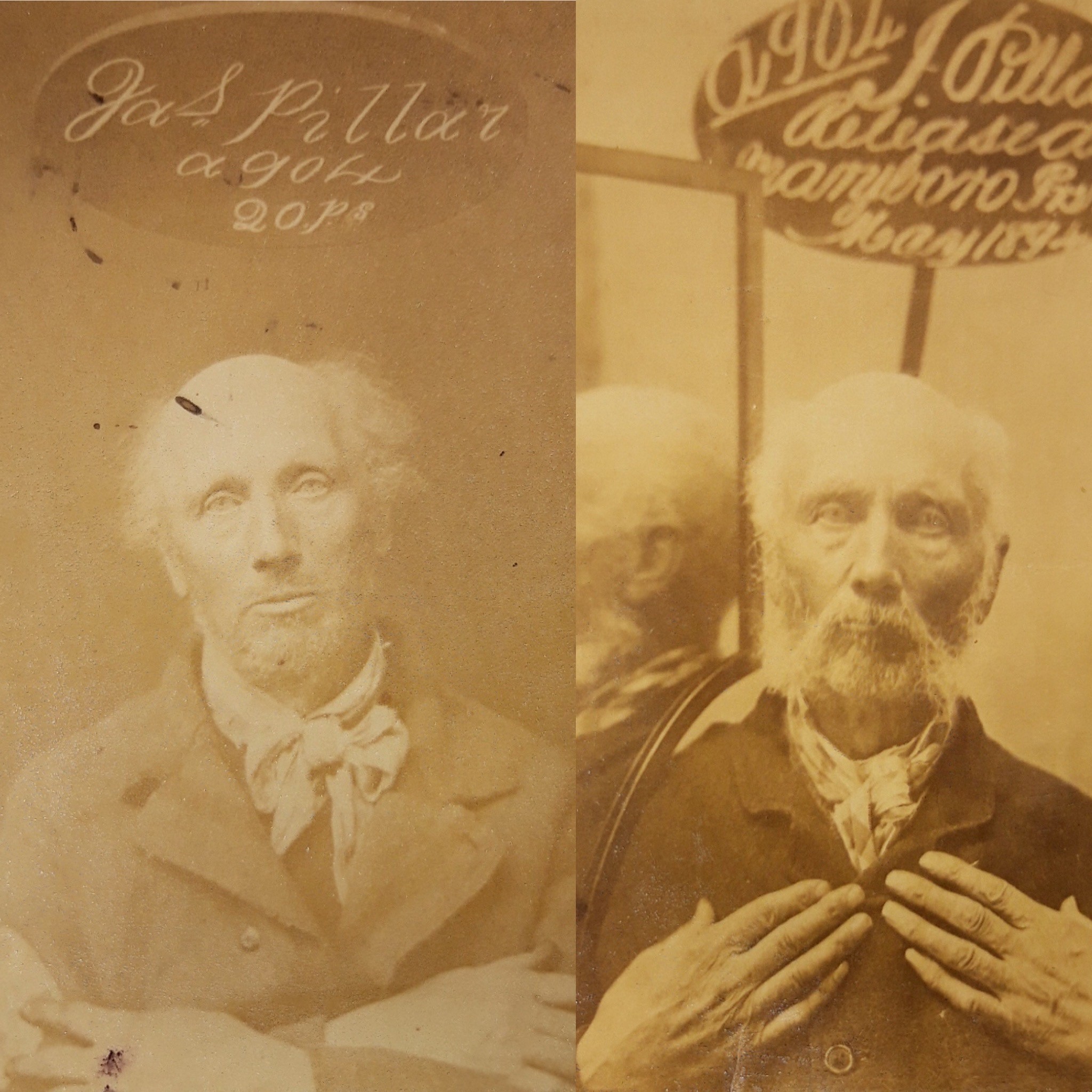

To mark our contribution to this year’s Pride Month we currently have a display of a penal file relating to the case of James Pillar, who was imprisoned as a result of a major scandal in Ireland, the Dublin Castle Scandal of 1884. James Pillar’s penal file (ref. GPB/PEN/ 1895/54) gives an insight into life in prison with photographs taken at the beginning and end of his incarceration showing how dramatically he had aged in less than ten years. Guest blogger Brian Crowley, Curator of Collections for Kilmainham Gaol Museum and the Pearse Museum expands on the background of this case and the fate of those involved.

‘We’ve seen the Pillars tumble’[1]: The fall of James Pillar

At the start of 1884, 63-year-old James Pillar appeared to be the model of Victorian respectability. Originally from Co. Tyrone, he ran a successful grocery and wine merchant business at 56 Rathmines Road. A committed member of the Quaker community in Dublin, he was married with three children and lived in a comfortable home in Palmerston Park. By the end of that year however, Pillar’s life lay in ruins. A bitter political war between the Home Rule movement and the British administration in Ireland inadvertently led to his exposure as a leading figure in Dublin’s secret male homosexual community. The resulting scandal proved devastating for those caught up in it.

Despite the fact Charles Stewart Parnell, the head of the Home Rule Party, had reached an agreement with the Liberal Prime Minister Gladstone in 1882 to work together to achieve Home Rule for Ireland, relations between Parnell’s movement and the British administration based in Dublin Castle remained deeply antagonistic. Parnell’s own newspaper, United Ireland, was edited by William O’Brien M.P. and was fiercely critical of the way Ireland was ruled, and used its columns to make bitter, and often personal, attacks on those involved in the administration. Dublin Castle responded with numerous attempts to supress the newspaper and prevent its distribution. It was against this backdrop that another Home Rule M.P., Tim Healy, decided to use the columns of the United Ireland to attack members of the administration on the basis of their private lives and morals.

One of Healy’s targets was James Ellis French, Director of Detectives with the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and County Inspector for Cork. Rumours had been circulating that he had sexual relations with other men, but Healy became the first journalist to allude to this in print when he linked French’s name with that of James Corry Connellan, a former Irish Inspector General of Prisons who fled the jurisdiction in the 1860s to avoid his own same-sex activities being exposed. French came under pressure from his superiors to sue for libel in order to both refute the charges and potentially destroy the newspaper with a ruinous financial judgement against them.

Faced with the prospect of his newspaper being sued, William O’Brien hired a disgraced former Scotland Yard detective named John Meikeljohn. As Meikeljohn began to investigate Dublin’s gay underground, he discovered that not only was French involved in homosexual activity, but he was also part of a whole network of gay men who were active in the city’s gay underground. It included people from every social strata, including George C. Cornwall, the Secretary of the General Post Office of Ireland. O’Brien now decided that, rather than retreat from the paper’s accusations against French reach a settlement, he would begin a campaign against him and Cornwall in print and depict them as emblematic of the moral corruption at the heart of Dublin Castle. By this stage French suffered what appears to have been a nervous breakdown, so it was Cornwall who ended up pursuing the libel case against O’Brien and the United Ireland.

The two sides met in the Four Courts on 2 July, 1884. Any hope Cornwall may have had of victory were quickly dashed when O’Brien’s defence team produced three men who had been pressured by Meikeljohn into testifying about sexual encounters they had had with Cornwall. Over the course of the trial they also exposed a number of other men in their circle. Judgement was given in favour of O’Brien who was hailed as a defender of Irish purity in the face of the corrupt and degenerate British regime.

As bonfires burned in celebration of his victory, panic spread throughout Dublin’s gay community. Many of those who could flee Ireland did so, including Richard Boyle, a member of an Irish banking dynasty and a former head of the Irish Stock Exchange. Cornwall and French were arrested and sent to Kilmainham Gaol to await trial along with six other men, including James Pillar. The other accused men included two military officers, Captain Martin Kirwan and Surgeon-Major Albert de Fernandez. Another man, Johnstone Lyttle, was a clerk, as were a number of the men who had agreed to testify against their former friend. Robert Fowler and Daniel Considine were two poor and elderly men who were accused of engaging in acts of buggery and allowing their tenement rooms on Golden Lane and Great Ship Street to be used by men for disorderly purposes. James Pillar was charged with a number of instances of committing buggery and it seems that, like Fowler and Considine, he also allowed men and male prostitutes to use his premises for their assignations.

The criminal trial took place in Green Street Courthouse and it is impossible to imagine just how humiliating and shameful it must have been for Pillar and the other men to have the intimate details of their private lives laid bare in a public court. However the trials also revealed a rare glimpse into the hidden world of gay life in Dublin in the 1880s. There were musical evenings in different men’s homes, parties in the tenement rooms of Considine and Fowler, trysts in St. Stephen’s Green, and sexual encounters in the Botanic Gardens. The extent of this activity suggests that the men believed, provided they used the utmost discretion, the authorities would not pursue them.

Malcolm Johnston, one of the men who gave evidence against the accused, described arranging a ‘drag ball’ where many of the male guests dressed as women. It was held in his father’s absence in his family home on Clyde Road in the wealthy suburb of Ballsbridge, and was attended by at least one clergyman from both of the main churches. He also listed some of the feminine nicknames the men used for one another. He was called ‘Conny’ or ‘Lady Constance Clyde’ or sometimes the ‘Marchioness of Dame Street’; Cornwall was ‘The Duchess’; Kirwan was ‘Lizzie’, while Fernandez was called ‘Mrs. F’. Robert Fowler was called ‘Ma Fowler’ and James Pillar was referred to as ‘Pa’ or ‘Papa’. Pillar’s nickname reflects the fact that he was one of the older men, but also perhaps that he had a senior position within the informal network.

Significantly, when the judge at Pillar’s trial, Mr. Baron Dowse, gave his summing up he made note of the fact that Pillar’s name was mentioned in the cases of all the other men, and it seems that he was a key figure in connecting the men with one other.

Initially, like the other accused men, Pillar pleaded not guilty. However, he seems to have had a change of heart and subsequently entered a guilty plea, the only one of the men to do so. As a result he was found guilty of just one felony charge of buggery, and all the other charges were dropped. He was sentenced to a life term of 20 years. Proving in a court of law that an act of buggery had taken place was incredibly difficult and Pillar was the only one of the men to be convicted of the more serious crime. French was given two years for conspiracy to commit buggery, while Considine and Fowler also received two years on charges of keeping a disorderly house. Why Pillar changed his plea is not clear, but given that he appears to have had a deep and genuine religious faith, he have decided to plead guilty as a sincere act of conscience.

Pillar served the first two years in Mountjoy before being later transferred to Maryborough (now Portlaoise) Prison. He would have been considered quite an old prisoner to be starting a sentence, and seems to have suffered from rheumatism and a number of other ailments. During his trial, the newspapers mentioned that he was a much older man, but he is also described as ‘fresh-complexioned’ and that he wore a brown wig and was ‘most respectably attired’. However in the mugshot taken of him on entering the convict prison system it is clear that the stress of the trial and public opprobrium directed towards him had taken a toll and he looks bedraggled and worn. His convict file records that, due to his age and state of health, he was later classified as being fit for only the lightest type of work suitable for an ‘invalid prisoner’. This included tasks such as sewing, darning and ‘teasing’ horse hair for use in mattresses. This is borne out by the one misdemeanor recorded against him, that he lent scissors to a fellow prisoner with whom he was working in contravention of the prison rules.

Pillar was married with three children, but his main correspondent and visitor during his time in prison seems to have been his son Charles Henry Pillar. Prisoner visits were severely limited at that time, and James Pillar usually received only one or two a year. Although his name was officially removed from the membership list of the Quaker meeting he attended, he seems to have retained some contact with his Quaker brethren. As he could not attend any Quaker meetings, he was given permission to attend the Presbyterian services instead. In 1890 he was allowed to read his own books, and these seem to include Quaker publications. Throughout this period his health remained poor, and there is a reference to him ‘a feeble old man showing symptoms of cerebral disease’, suggesting that he may have been developing some form of dementia.

He petitioned for release on the grounds of ill-health and, having served approximately half of his sentence, he was discharged on licence in May 1894. His wife Susanna, who was resident in their premises on Rathmines Road, had passed away in February that year. James Pillar appears to have settled in Co. Wicklow on his release but he died in Mercers Hospital in Dublin on 24 November, 1894.

Brian Crowley, Curator of Collections for Kilmainham Gaol Museum and the Pearse Museum

Twitter: @OPWkilmainham

Myles Dungan, Mr. Parnell’s Rottweiler, Censorship and the United Ireland Newspaper, 1881-1891 (Dublin, 2014)

Brian Lacey, Terrible Queer Creatures, Homosexuality in Irish History, (Dublin 2008)

Rictor Norton (Ed.), “The Dublin Scandals, 1884”, 13 March 2019, http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1884dub.htm.

The Dublin Castle scandal’s “Unspeakable Crime” (1884)

[1] from ‘Hold Your Nose! A Collection of Sanitary Songs Intended for the Disinfection of Dublin Castle’ (1884)