Behind the Scenes

Behind the Scenes: The Distress Papers

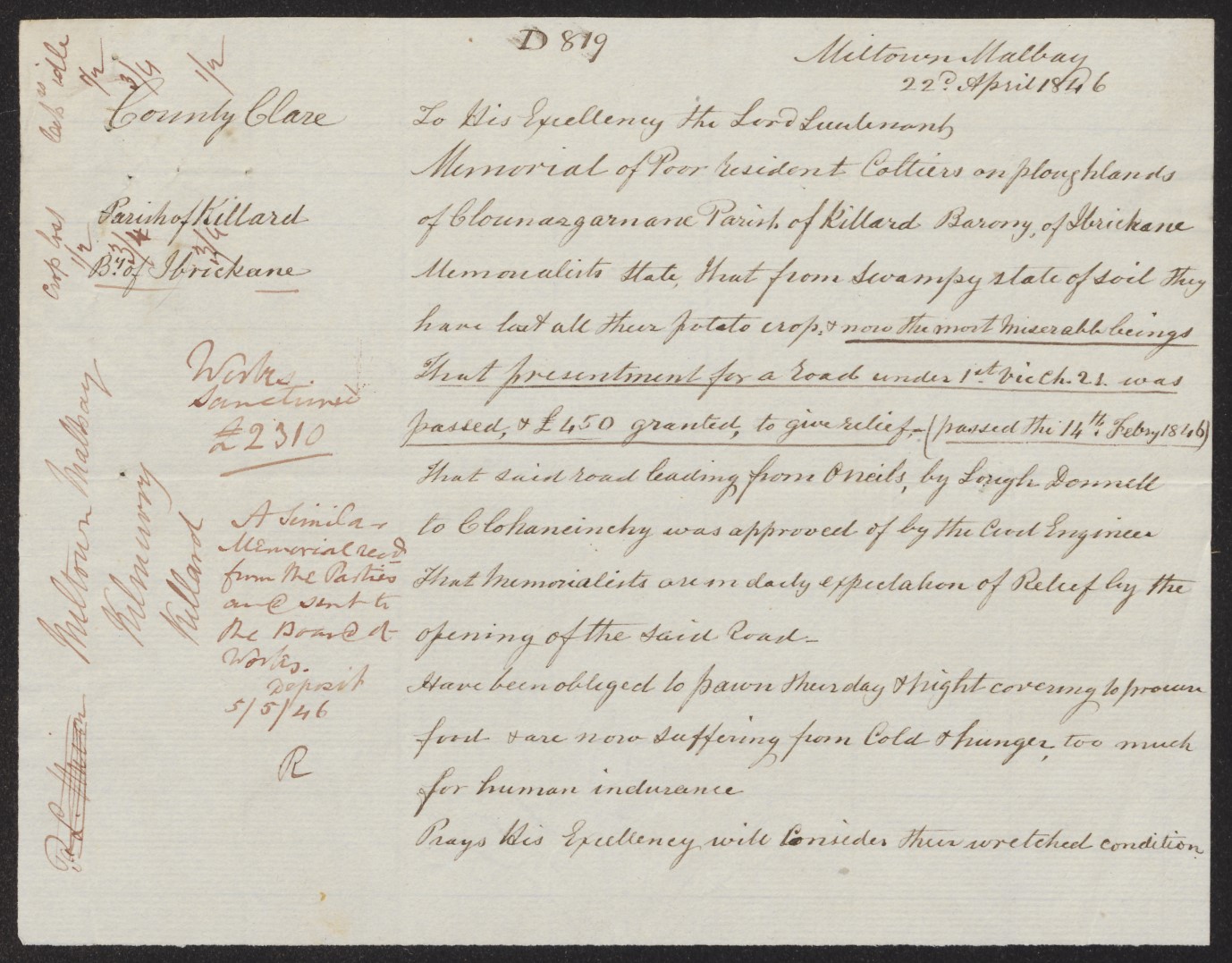

They have been obliged to pawn their day and night covering to provide food and are now suffering from cold and hunger [to] much for human [indurance].

This heartrending quote appears in a petition dated 22 April 1846 (ref. NAI/Famine Distress Papers/D819/1) from the tenants of Killard, county Clare to the Lord Lieutenant, in which they describe their wretched condition and implore Queen Victoria’s representative in Ireland for assistance. This petition and many others like it can be found in the Distress Papers, a record series which forms part of the Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers. The latter collection is one of the most valuable sources for research on Ireland in the 19th and early 20th centuries and is held in the National Archives – www.nationalarchives.ie –on Bishop Street in Dublin.

Images of the Distress Papers have recently featured both on the RTÉ History Show’s Twitter account – @RTEHistoryShow – and on the Great Irish Famine project at www.rte.ie/history/the-great-irish-famine, an online collaboration between University College Cork and RTÉ and generously supported by the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. Designed as a companion website to ‘The Great Hunger’ documentary, this ongoing web project displays contemporary Famine-era documents which are explained and contextualised in articles by historians of the period and further illustrated by maps from the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine.

So how and why did the Distress Papers come into being? Such was the volume of letters, reports and petitions pouring into the Chief Secretary’s Office requesting funds and assistance during the Famine that the authorities in Dublin Castle deemed it necessary to give separate treatment to incoming papers relating to distress. Thus was born the Distress Papers, a distinct sub-series to the Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers, which was begun in March 1846 in an attempt to tackle the avalanche of pleas for aid, many of which came from the west and south of the country, regions which were being ravaged at the time by the Famine.

What do the Distress Papers actually contain? Their content tends to be routine for the period and includes some of the following document types:

- Reports on the extent of distress among communities across the country

- Letters relating to the establishment of relief committees

- Applications from various localities for funds granted under famine relief legislation

- Letters from the British Treasury concerning the spending of funds

- Correspondence from the Relief Commission and the Office of Public Works recommending specific projects for funding

What can the Distress Papers tell us? This sub-series is invaluable in helping us to better understand the Famine’s impact on Ireland’s people and landscape and the reasons for the cataclysmic changes wrought in Irish society in less than a decade. The Famine and its consequences permanently changed the island’s political and cultural landscape, resulting in over one million deaths and the emigration of an estimated two million people. It was the catalyst for a century-long demographic decline, with Ireland’s population falling by 20–25% due to death and emigration.

The Distress Papers can be used for comparative analysis as they illustrate how uneven the Famine’s impact was felt around the country and are a key resource for those studying the progress and impact of the Famine in particular geographical areas. They tell of the different Famine experiences of the eastern and midland counties – less badly affected than those in the west and south, which reported calamitous death tolls and the decimation of many rural communities.

The Distress Papers also tell us the stories of the people behind the grim statistics. They give a voice to the dying and the poor whose lot it often was to remain invisible or voiceless in official records. Behind the dry bureaucratic language used in the records lies all too real human suffering and tragedy. The Distress Papers, in common with those of the Famine Relief Commission, the Poor Law Commission, the Chief Secretary’s Office and the Office of Public Works, provide a variety of perspectives on the Famine. They enable an analysis both of the extent of distress and of government response at local level, as well as the degree to which prevailing philosophies of government and economics had an impact on the administration of relief.

On another and no less important level, the searing first-hand accounts of privation and destitution to be found in many of the Distress Papers place the human experience of the Famine centre stage. In doing so they ensure that the voices of its victims continue to resonate to the present day.

Elizabeth McEvoy, Archivist