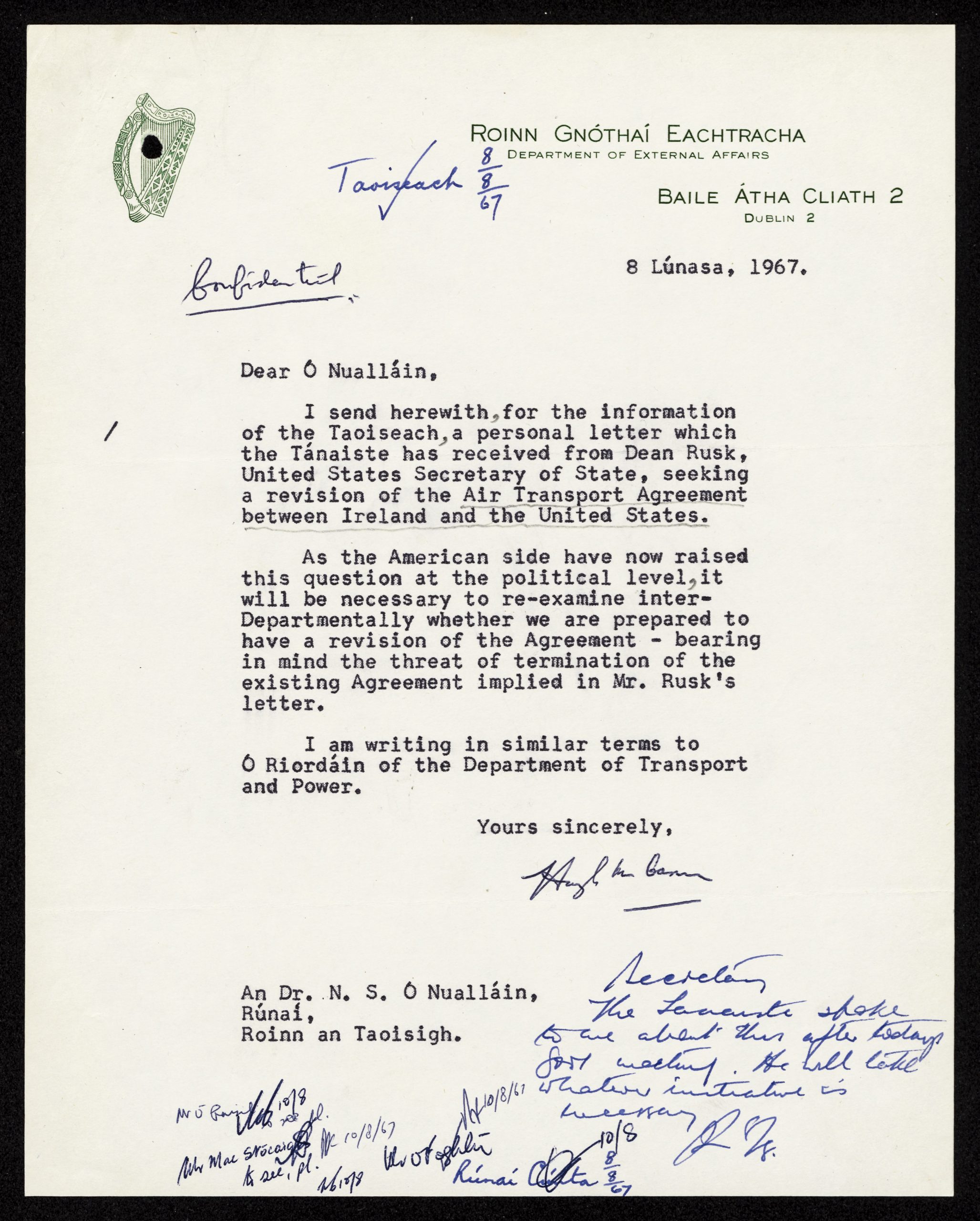

File in Focus: A worrying note from the Secretary General of the Department of External Affairs for the attention of Taoiseach Jack Lynch, 1967

In the late-1960s Dublin and Washington were on a collision course over transatlantic aviation.

Since the end of the Second World War United States aircraft on transatlantic passenger flights could land at Shannon Airport. They had not permission under the 1945 Ireland-United States Air Transport Agreement to land at Dublin airport.

The big United States carriers of the 1960s – Pan American Airlines and Trans World Airlines – wanted access to Dublin. They felt it would give them access to Ireland’s main tourist attractions and that it would allow them to compete more equally with Aer Lingus on the increasingly busy transatlantic routes into Ireland.

By the late 1960s, under the influence of powerful airline bosses, including Juan Trippe of Pan-Am, United States Secretary of State Dean Rusk put pressure on Ireland’s Minister for External Affairs Frank Aiken to have the 1945 Agreement revised to allow American carriers access to Dublin to compete with Aer Lingus.

On receipt of Rusk’s letter, Secretary of the Department of External Affairs Hugh McCann explained in this 8 August 1967 letter (ref. NAI, TSCH 98/6/95) to Cabinet Secretary and Secretary of the Department of the Taoiseach Dr Nicolás Ó Nualláin (Nicholas Nolan) that the ‘Dublin Landing Rights’ issue had been raised to a ‘political level’. Dublin needed to act and refocus their strategy in response to Washington’s raising the stakes.

The worrying point in McCann’s letter was that Rusk had threatened to terminate the 1945 Air Transport Agreement if Dublin did not alter its position. That would prevent Aer Lingus from landing at JFK, Boston, and Chicago and the other destinations on its prestige transatlantic service.

The late 1960s were the golden age of transatlantic aviation. Aer Lingus flew state of the art Boeing 707s across the Atlantic and was soon to introduce Boeing’s 747 on flights to North America. The Irish airline had even taken out options on purchasing two Boeing 2707s, the ill-fated Boeing competitor to the Anglo-French supersonic concord.

There was thus much at stake on 8 August 1967 when McCann wrote his note to Ó Nualláin.

Taoiseach Jack Lynch read the note that day and in a handwritten annotation on the bottom right-hand corner wrote to Ó Nualláin that he and Aiken had spoken and that Aiken would ‘take whatever initiative is necessary’.

Aiken played hardball with the State Department and Dublin continued to hold out. Aer Lingus had a small route share on the Atlantic, buts its customers – many of whom were Irish-Americans – were loyal. Dublin might win out.

Washington would not give in. Under relentless pressure and the eventual termination for a brief period of Aer Lingus’ landing rights at JFK in the early 1970s, Dublin was ultimately forced to allow Pan-Am and TWA to land at Dublin.

The irony of this game of power-politics was that when the two American carriers got their landing rights in Dublin TWA and Pan-Am showed little interest in the service.

Michael Kennedy is the Executive Editor of the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (DIFP) series. He has for thirty years researched and published on the history of Ireland foreign policy. DIFP publishes archival material relating to Ireland’s foreign relations since 1919. It is a partnership between the Royal Irish Academy, the National Archives and the Department of Foreign Affairs: www.difp.ie. Documents on Irish Foreign Policy Vol. XIII: 1965-1969 is published by the Royal Irish Academy.

This note is included in DIFP XIII as No. 332.