Singing Sedition: ballads and verse in the age of O’Connell

An exhibition of ballad sheets and political verses of the 1820s – 1830s from our Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers (CSORP), curated by archivist, Nigel Johnston.

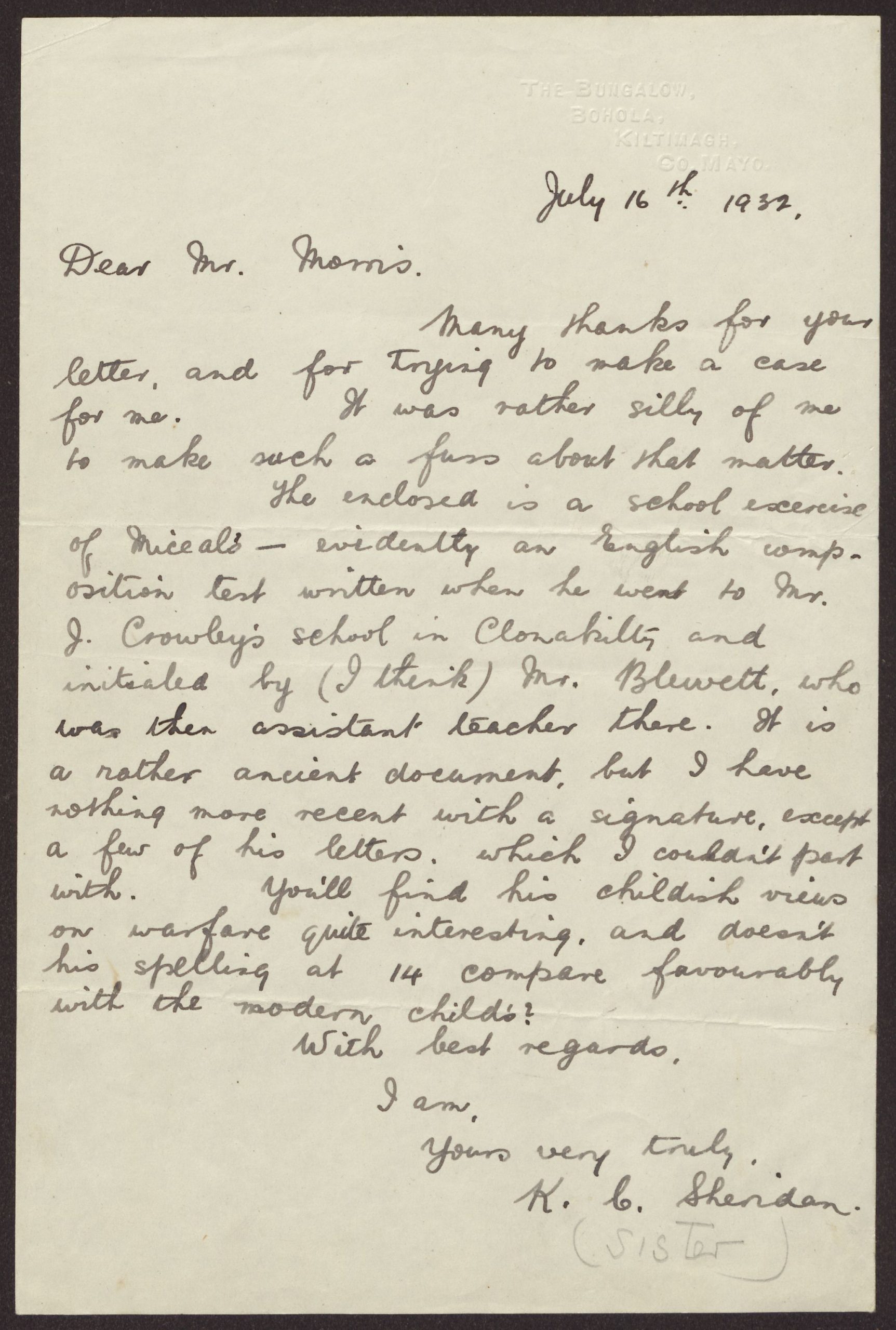

The small collection of ballad sheets and political verses are amongst the most fascinating documents found in the Chief Secretary Office Registered Papers (CSORP). Fortunately, a good selection of original material survives due to the vigilant reporting of local authorities on the activities of ballad sheet vendors and singers. Submissions to Dublin Castle by magistrates and police officers generally included the original ballad sheet together with the written report or letter; this practice ensured we have access to the broader context of the transaction.1 Most ballads are printed with title and include a woodcut impression as a visual accompaniment to the text. They are usually printed on low-grade paper, single side, and formed in long narrow strips for easy circulation. Often distributed by travelling sellers or singers at fairs or markets, they offer an economically viable mode from which to communicate the ideas of revolution to a largely illiterate population.2 Almost all are compiled by anonymous authors, although a small, but significant, number include the printer’s name or place of publication. Production of ballad sheets in Ireland reached a peak in the nineteenth century with the earliest known example dating from 1626. The exhibits highlighted relate to the 1820s and 1830s, a period in which ’The Liberator’ Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847), focused his energy on gaining religious and civil liberty for Roman Catholics and campaigning for a repeal of the political union with Great Britain.

Arising out of unofficial channels ballad sheets express the opinion and sentiment of the ordinary people of nineteenth century Ireland, often revealing their private attitudes to the great questions of society, politics and religion. As a medium of communication from an otherwise unrepresented class, such verses and songs provide a critical counterbalance to the views of the landed elite. It has been noted, for example, that a public performance by a ballad singer might exert a powerful influence on its listeners, guiding and shaping ‘belief, thought, action and attitude’.4 Certain types of ballads may not be readily accessible to the modern reader, since they can contain cryptic references to local persons or events.

Amongst the most common sentiments articulated by ballad authors are those connected with romantic ideas about Irish nationhood. Early impulses in favour of a separate and independent nation free from the influence of Great Britain are evident in a ballad like ‘A Lamentation on the State of Ireland’ (ref. CSO/RP/OR/1832/876/6) which is written entirely in the Gaelic language. A production like this certainly would have a strong resonance with people living in localities where English was little known.

Quite apart from the printed ballad sheets of the CSORP, the collection contains a narrow but rich seam of documentary evidence relating to the activities of song vendors and narrators alike. During the troubled early decades of the nineteenth century the authorities in Dublin Castle were especially keen to curtail the dissemination of subversive material as well as restrict anti-government propaganda. In practice, of course, the law was implemented by the local magistrates and the police constabulary, the men on the ground in the different county parishes and baronies. Legal advice was sought in many instances by the constabulary on the thorny question of dealing with travellers, itinerants and hawkers, men and women whose behaviour or motives might arouse suspicion. In July 1831 for example, Chief Constable William Kelly of Gorey in County Wexford requested guidance from the law officers of the crown on dealing with ‘strangers’ in the neighbourhood, or such as were suspected of circulating ‘inflammatory’ songs. Such individuals, if allowed to continue undisturbed, he warned, might incite the lower orders to violence (ref. CSO/RP/1831/1834).

Seeking to raise the alarm in his own jurisdiction, William MacDougall of the city of Belfast, County Antrim, voiced considerable concern to government at the reprinting of a ‘vile’ publication containing ‘nothing but the Revolutionary principles and Rebellious Songs of 1798’. He complains that ‘itinerant Hawkers’ are engaged in the circulation of such material and asks that steps be taken to secure their arrest (ref. CSO/RP/CA/1826/32). In fact, a compilation or chapbook of musical pieces from the radical composers of the late eighteenth century was still in circulating as late as 1832, written under the pseudonym of ‘Billy Bluff’ (ref. CSO/RP/OR/1832/809). As with ‘The Man of the Law’ such literary offerings contained a most abrupt political message, one that was at variance with the accepted order and established political union. In this composition ‘Granu’ (Gráinne), an allegorical representation of Ireland, is portrayed as representing the Irish nation now under siege by England (John Bull).

From the perspective of the authorities, involvement in the narration or promotion of subversive ballad sheets was synonymous with treason. For example, suspicion was aroused over a man named Browning, a native of County Fermanagh, by the postmaster of that county in November 1829. In the event, an investigation was made of Browning and in his possession was found a number of seditious songs and poems, both in printed and manuscript form. It was concluded that his home was used as meeting place for disaffected persons (ref. CSO/RP/OR/1829/880). On various occasions too, reports reached Dublin Castle of certain individuals whose attitude and behaviour had the appearance of disloyalty. One such example is referred to in a joint affidavit of Richard Anderson and Edward Sanns of County Sligo, sworn in May 1828. Anderson and Sanns identify nine people from Ballymote, whom they accuse of singing a treasonable song at the wake of the late Harry Gallagher (ref. CSO/RP/1828/655). A near parallel is an affidavit of Thomas Taylor, washer of ore at Kildrum Mines, County Donegal, accusing one James Kennedy of singing a subversive ballad in October 1828 (ref. CSO/RP/1828/1693).

Arrest and imprisonment were usually the immediate consequences of the public performance of such censored material. In mid-1831, a female singer named Anne Rooney was accused of disturbing the peace of the town of Carlow, County Carlow. She is described as a ‘notorious vagrant going about singing Ballads of an inflammatory nature’ and was detained on grounds her recitals were calculated to ‘excite the minds of the lower orders’ (ref. CSO/RP/1831/1409). Rooney made a strong objection to her arrest by the police, a plea also advanced by Edmond Barry who was likewise brought into custody for ballad singing at Listowel Fair, County Kerry, in May 1832 (ref. CSO/RP/1832/2435). Official resistance to the activities of ballad singers, might, as was the case in Toomevara, County Tipperary, bring the constabulary and members of the lower orders into direct conflict. On the occasion in question, a countryman of the name of Patrick Gleeson was shot by the police following an attack on the police station. The confrontation was the direct result of the removal of a ballad singer from the barrack door (ref. CSO/RP/OR/1828/585). At the other end of the scale, the full force of the law was brought against Denis Ring of County Cork, ‘a vagrant ballad singer’. His case was referred to in a letter, likely to Dublin Castle, by J Bayley in August 1827. Bayley remarks the culprit was tried and sentenced to seven years’ transportation in Botany Bay (New South Wales, Australia) for ‘vending and singing Ballads of the most mischievous and evil tendency’. In his communication, Bayley urges that no legal concession be made to Ring and insisting that no heed be paid to any ‘interference or application in his behalf from the Popish association in Dublin’ (ref. CSO/RP/1827/1465).

Footnotes

1Murphy, Maura, “The ballad singer and the role of the seditious ballad in nineteenth-century Ireland: Dublin Castle’s view” in Ulster folklife magazine vol. 25 (1979), p79.

2G.D. Zimmermann, Songs of Irish Rebellion: Political Street Ballads and Rebel Songs 1780-1900, (Dublin, 1967), p9.

3 ‘The Seller to the Fair’ at: https://www.itma.ie/blog/the-seller-to-the-fair (accessed, 10 January 2020)

4 Neilands, Colin Watson, Irish broadside ballads in their social and historical contexts, thesis vol. 1: Queen’s University, Belfast, 1986, p.146.

5Comment contained in the Outrage Reports of 1833 (CSORP), likely a submission from Thomas Sloane of County Cork (papers for that year not listed yet); see https://www.itma.ie/blog/the-seller-to-the-fair

'Young Bony's Freedom' ref. CSO/RP/1831/172

Contemporary observers recognised that Ireland in the 1820s and 1830s was a nation in a profound state of political flux. Change was apparent on a number of different levels touching at once the great issues of Irish local and national politics. What was clear to contemporaries was the enormous public influence of Daniel O’Connell, a man celebrated variously as the ‘Liberator’ or ‘Emancipator’. His Ireland was one in search of change, in search of civil and religious liberty for Roman Catholics, and, finally, in search of a repeal of the Act of Union of 1801.

Of the ballads in the CSORP collection with a distinctly political flavour, a large proportion relate to the personage of O’Connell and his aspirations for the future of the nation of Ireland. Taken as a whole they offer a unique glimpse into the political mind-set of pre-famine Ireland.

Quite early in life O’Connell showed a penchant for matters legal and political. His empathy with the architects of the French Revolution, however, was restrained, and he enrolled in the Lawyers’ Artillery Corps in the late 1700 in defence of government. At the same time, he remained an enthusiastic advocate of the broader themes of national self-determination. The link in the popular mind between Ireland’s demand for a separate parliament and the victories gained over crowned heads by the charismatic leader of the French Revolution, Napoléon Bonaparte, were articulated in such ballads as ‘Young Bony’s Freedom’ (CSO/RP/1831/172). Followers of O’Connell who heard such works recited would no doubt have found some solace in the idea of a liberated Ireland free from outside influence.

'The Land of Shillelagh and O'Connell' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1831/172

Whether or not by his activities in the 1820s, O’Connell ‘planted a tree’ as is alleged in the ballad ‘The Land of Shillelagh & O’Connell’ (CSO/RP/OR/1831/172), he was certainly at the centre of Irish demands for political reform. From 1823 the Catholic Association was the driving force behind his general campaign for emancipation – that is the removal of certain political and legal disabilities affecting Irish Catholics. O’Connell’s great achievement was to harness mass agitation and graft a new found political assertiveness into Irish society.

'O'Connell's New Song on Emancipation' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1830/679

Of greater significance for the broader movement was O’Connell’s decisive victory in the Clare election of 1828. He seized the opportunity to stand against William Vesey Fitzgerald (Conservative MP for Clare), a public representative who was forced to seek re-election on account of his acceptance of a post under government and O’Connell secured a conclusive majority of more than 1000 votes in the contest.1 In the event, he was forced by royal command to seek a formal re-election, and in February 1830 he became the first ever Catholic to take his seat in the House of Commons. Ultimately, his success in the Clare election paved the way for the granting of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. This pivotal moment in Irish history is celebrated in the ballad ‘O’Connell’s New Song On Emancipation’ (CSO/RP/OR/1830/679). Here recognition is given to the aid of some “7 million Catholics” and to the backing of key pro-Catholic allies like O’Gorman Mahon, Thomas Steele and Richard Lalor Sheil, and of course, John Lawless of the “Order of Liberators”.

Footnote

- George Boyce, Nineteenth Century Ireland, (Dublin, 2005), p.57

'O'Connell's Welcome to Parliament' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1830/679

Set in the same general context of ‘O’Connell’s New Song on Emancipation’ is the rousing ‘O’Connell’s Welcome to Parliament’ (CSO/RP/OR/1830/679) which invites listeners to raise their voices to the Catholic Association “Which crushed the knaves that made us slaves”.

'A Pill for O'Brien' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1831/1095/3

Proof that County Clare remained a hotbed of political activity in O’Connell’s time is supplied by a further couple of ballad sheets in the collection. The title ‘A Pill for O’Brien’ appears to refer to the election victory won by Maurice O’Connell, brother of Daniel, over Sir Edward O’Brien in the County Clare elections of 1831.1 Making use of quite emotive language and recalling the penal laws of old, the author exhorts its hearers to “Expel those cursed Tyrants From this Country” and fix your vote on “Young Maurice”, a true advocate of the Catholic cause (CSO/RP/OR/1831/1095/3).

Footnote

1. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/constituencies/ennis

'Ennis's Repeal of the Union' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1831/417

After gaining emancipation, O’Connell redoubled his energy towards securing a repeal of the act of union and bringing back an Irish parliament. The Act of Union of 1801 had merged the parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland and was heavily supported by landed interest in both countries, and crucially, by the aristocracy in the north of Ireland. In view of the opposition shown by northern Protestants ‘Ennis’s Repeal of the Union’ (CSO/RP/OR/1831/417) is oddly daubed with optimism, since it asserts on that critical issue “Orange and Green they both do agree”.

'A New Song on the Repeal of the Union' ref. CSO/RP/1831/542

If repeal could be wrested from the Crown and Commons then Ireland would advance and grow, so said the proponents of that measure. Prosperity would follow and the ”tradesman & labourers would flourish as before…”, at least so writes the author of ‘A New Song on the Repeal of the Union’ (CSO/RP/1831/542). Yet, without any concrete prospect of immediate success, O’Connell maintained his campaign for repeal during the 1830s. By doing so he demonstrated a persistent determination and self-belief. True, he did enter for a period into a compact with the Whig party in the mid-1830s, seeking concessions and reforms, but he later returned with renewed vigour to the great political question.

'O'Connell's Prayer and Steel's Amen' ref. CSO/RP/1831/542

A degree of flippancy is apparent in the production entitled ‘O’Connell’s Prayer and Steel’s Amen’ (CSO/RP/1831/542) with the former telling the latter in this pretended exchange that repeal will be won “…in less than three years, If truth I don’t tell, you may cut off both my ears”! While contemporary observers differed in their opinion of the man, O’Connell will be remembered as a formidable political leader who used every means in his power to advance the duel objectives of reform and repeal in Ireland.

'Lord F[arnham]'s Converts' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1831/172

In the age of O’Connell the bulk of the nation gave the appearance of a people heavily attached to formal religion. For those of the Roman Catholic majority the great overriding issues of politics and economy frequently blended together with concerns of a pious nature to inform and direct social action. Nowhere was this more evident than in the veto controversy which vexed political opinion between 1807 and 1823. Put concisely, the issue arose in the context of some proposed securities laid before Parliament to limit the potential consequences of a grant of Catholic emancipation. To protect the ascendency against the threat of Catholic political dominance in Ireland, it was asserted that the intended measure should be accompanied with a government veto on the appointment of Catholic bishops, payment of priests by the state, and formal oversight by government of correspondence between the papacy and Irish Catholic hierarchy. The matter proved to be a divisive one for the Irish Catholic body, with O’Connell coming out in strong opposition to the proposals, despite support for an accommodation by certain more conservative elements.

From the 1820s onwards denominational competition was intensified by the arrival of the so called Second Reformation. In essence, the movement was a concerted attempt by a number of different Protestant agencies to convert the Roman Catholic population of Ireland. Conflict between the main denominational parties was the immediate outcome as Catholic and Protestant leaders became embroiled in theological discussion in newspapers, pamphlets and public debate. Since education was used as a means to promote the reformation, it became a hotly contested battleground between the opposing groups, with O’Connell accusing the Bible schools of proselytism. Others accused the movement of exerting pressure on Catholic tenants to send their children to evangelical schools, or of using food as an incentives to convert. The Second Reformation was patronised by a number of key Irish landed aristocrats such as Lord Farnham from County Cavan, a place where a considerable number of converts from Catholicism were claimed.1 In the ballad entitled ‘Lord F[arnham]’s Converts’ (CSO/RP/OR/1831/172) the author enthuses “Ye Catholics of fame, ye may thank the Great Supreme, that your church is lately cleared of rotten members”.

Footnote

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/second-reformation-1822-1869

'On Doctor Doyle' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1831/172

By the same token, the title ‘On Doctor Doyle’ (CSO/RP/OR/1831/172) celebrates the firm opposition given the Bible movement by James Warren Doyle, Catholic Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin, by offering correction to Lord Farnham whose ‘error he exposed’. With a hint of polemic, the ballad writer alleges the scriptures promoted by the evangelical Lady Lucy Barry (of Newtownbarry in County Wexford) failed to produce genuine results or longstanding effect

'New Sheela na Guira' ref. CSO/RP/1821/1309

Ballads in support of the Protestant or evangelical interest are generally less common. A copy of a ballad ‘Up Orangemen Up’ by a Protestant author named David McKinley was posted in the town of Enniskillen in County Fermanagh early in the year 1829 (ref. CSO/RP/OR/1829/139). By binding together a variety of charges against Catholicism in Ireland including ‘base Superstition, and Priestcraft, and Crime’, McKinley’s polemical work likely contributed more than a little to the denominational tensions that marked the province of Ulster at this period. Opposition to such material is not difficult to find.Catholic spirits were further disturbed by the wide dissemination of the baneful prophecies of Pastorini who predicted the overthrow of Protestantism in the mid-1820s. Indeed, through the release of parts of that prophetic work in cheap tracts and handbills, the Irish peasantry were kept in a constant state of ferment.1 A reference to this prediction is made in the ballad ‘New Sheela na Guira’ (CSO/RP/1821/1309) in which the author makes the following exhortation:

‘Ye children of Erin cheer up, be alive, For all Prophets agree for the year twenty-five, Each tun-bellied locust shall weep on that day. That Erin’s brave sons shall wipe sorrow away’

Footnote

- James S. Donnelly jnr., ‘Pastorini and Captain Rock: Millenarianism and Sectarianism in the Rockite movement of 1821-4’, in Samuel Clark and James S. Donnelly jnr, eds., Irish Peasants: Violence and Political Unrest 1780-1914 (1983, Wisconsin), pp.110-111

'The Battle of Muff' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1830/221

In view of the presence of such rivalry between adherents of the principle faiths, outright social conflict was the frequent result. An interesting example is a ballad entitled ‘The Battle of Muff’ (CSO/RP/OR/1830/221). It concerns a sectarian confrontation that took place in a village of that name in County Cavan in August 1830. On the occasion in question a number of lives were lost when agitators of the Catholic persuasion directed their anger against their Protestant opponents, leaving ‘orange lodges blazing’ and their victims ‘raving’.

'The Downfall of the Tithes' ref. CSO/RP/1832/2928

Probably the largest issue to unsettle the Irish landscape in the second and third decades of the nineteenth century was that of tithes. Put simply, these were the financial demands placed on tenants and landholders for the support of the clergy of the Church of Ireland. At a most basic level, the burden of this tax imposed by the ruling elite fell largely upon the poor Catholic tenant who did not subscribe to the established church.

Agitation against tithes reached its climax during the so called tithe war of 1830-33. Ballads like ‘The Downfall of the Tithes’ (CSO/RP/1832/2928 ) resorts to the use of heavily sectarian language in resistance to the tithe charge. The writer of that piece anticipates a battle to liberate ‘Old Ireland’ from the grasp of ‘orange tritors (sic)’ or ‘die like heroes on Slievenamon’. Indeed, mention of Mount Slievenamon recalls a very bloody encounters in that vicinity between crown forces in support of the process server and the country people. The clash happened on the townland of Carrickshock in County Kilkenny on December 1831. On the day in question about fourteen policemen were killed and a similar number injured. In addition, a small number of countrymen were also amongst the causalities.1

Footnote

- http://www.traceyclann.com/files/carrickshock.pdf

'Inhuman Massacre in Newtownbarry' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1831/172

Another major incident commemorated in song as an ‘Inhuman Massacre in Newtownbarry’ (CSO/RP/OR/1831/172) draws our attention to the killing of fourteen country people by yeomanry during an enforcement of tithe demands in County Wexford.1

Footnote

- https://mylesdungan.com/2013/06/14/on-this-day-18-june-1831-the-newtownbarry-massacre-the-tithe-war/

'Corn Meeting on Tithes' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1832/867

That same incident, receives a mention in ‘Corn Meeting On Tithes’ ( CSO/RP/OR/1832/867), with the added admission by the writer that the tithes at Newtownbarry ‘made me bleed’.

'The Doneraile Conspiracy' ref. CSO/RP/OR/1830/177

O’Connell’s triumphs were much esteemed across the ballad sheet trade. In recognition of his political efforts to reform ecclesiastical demands, one such composition carried the title ‘Drink A Health to O’Connell who has got the Tythes down’ (CSO/RP/OR/1832/876). His work as a barrister was to reach the status of legend, however, in view of his involvement in a number of high profile murder cases such as that of Carrickshock, noted above. Similarly, his successful defence of a number of men linked to a murder plot in north County Cork is fêted in ‘The Doneraile Conspiracy’ (CSO/RP/OR/1830/177).1 With a slight aimed directly at the ascendency, the author of the ballad observes ‘in spite of all their hellish schemes O’Connell set us free’.

Footnote

- http://clarechampion.ie/the-doneraile-conspiracy/