As part of the VOICES Project the team has set out to digitise over 1,000 Irish Chancery documents which feature women as plaintiffs or defendants. By launching this initiative in collaboration with NAI to digitise and VRTI to platform a sample of documents, VOICES is putting early modern Irish women’s stories into the spotlight in a way that was previously unimaginable.

This curated collection highlights the diversity of roles women played in early modern Ireland, whether victim or offender, landlord or tenant, wealthy or poor. The cases demonstrate how women could exercise tremendous power and agency in legal settings, but also how they could find themselves powerless and marginalised in a patriarchal system.

A Rich Tapestry of Women’s Stories

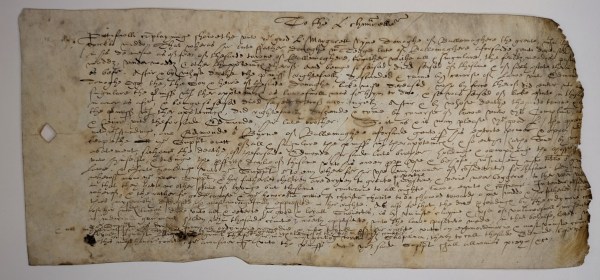

One such woman was Margaret Ní Dhonnchadha [Margarett nyne Donoghe], a widow from county Wicklow. Margaret’s lodged two Bills of Complaint regarding her inheritance of family lands. Her first Bill appeals to the Lord Chancellor with emotive rhetoric, drawing upon his reputation as a protector of the weak and defenceless. Margaret and “her fatherless children are driven to great poverty, misery, and very near beggary […] in that they have no other stay of living” than the stolen land, and so in the name of “God’s cause and your honourable pity of Christian charity to be showed towards a poor widow and her fatherless children thus miserably distressed, and most wrongfully oppressed”, the court was asked to find in her favour.

Margaret’s second Bill attempts to play on anti-Irish prejudice rather than the conscience of the court. It emphasises how Edmond O’Byrne appropriated her land “without just title, but only by strong hand according the rude and base manner of that country”. In the late 16th century Wicklow was a threatening and rebellious wilderness from the perspective of the nearby Dublin authorities.

What is really interesting here is that we see Margaret Ní Dhonnchadha – ostensibly a Gaelic Irish woman – recognising and seeking to exploit the fact that the legal system imported by the English stood to benefit her more than her native customs. English common law and equity ensured the right of widows and heiresses – under certain conditions – to inherit land. According to Irish legal custom, only men could own land. Customs varied around the island, but in partible inheritance was practiced and land would always find itself in the hands of a man. According to Irish legal custom, O’Byrne was probably in the right.

A powerful widow

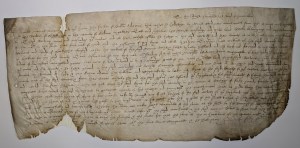

In other cases, we find women wielding the power, seizing land and property under disputed circumstances. One such woman was Dame Margaret Butler, “Lady of Lackagh” in County Kildare. Dame Margaret had been married to two powerful men from well-known families: first Rory Caoch O’More, and later Sir Maurice FitzGerald of Lackagh. By the time she appeared in Chancery as a widow, between 1575 and 1601, she was attempting to consolidate her inherited properties to maximise their profitability, and occasionally impinging upon the rights and customs of the local populace.

One case involves John Forster, a Dublin Alderman, who claimed that the rectory of Lackagh had been demised to him by the Crown. He and his tenants had enjoyed customary pasturing and turf-cutting rights on the “Commons” of Lackagh for many years. Dame Margaret, he claimed, had entered the glebe lands and ejected Forster and his tenants, and seized their cattle. She even proclaimed that no tenant in the parish should take any of the tithes of the rectory upon pain of a fine. Forster’s complaint highlights Dame Margaret’s aggressive tactics in asserting her control over the land.

Similarly, Anne Ussher, a widow from Naas, complained that the same Margaret Butler had acted alongside her lessee James Gerrot to take an injunction against her, ejecting her from lands and a watermill inherited from her husband. Ussher emphasised the asymmetry of power which existed between herself and Butler; where the she was “a widow and a stranger having no alliance nor kindred in that shire”, Dame Margaret enjoyed “such great alliance, wealth, and kindred” in Kildare that there was no possibility for fair local mediation. Only the Chancery, that remote and impartial dispenser of justice, could be trusted to intercede for Anne Ussher.

Both cases involving the Dame Margaret Butler, Lady of Lackagh demonstrate the social and economic power that property-owning widows could wield in early modern Ireland. In Dame Margaret’s case, this power was exercised over men, both as “victims”, and as lackies in her efforts to expand her landholding and influence in Kildare.

Everyday disputes and domestic life

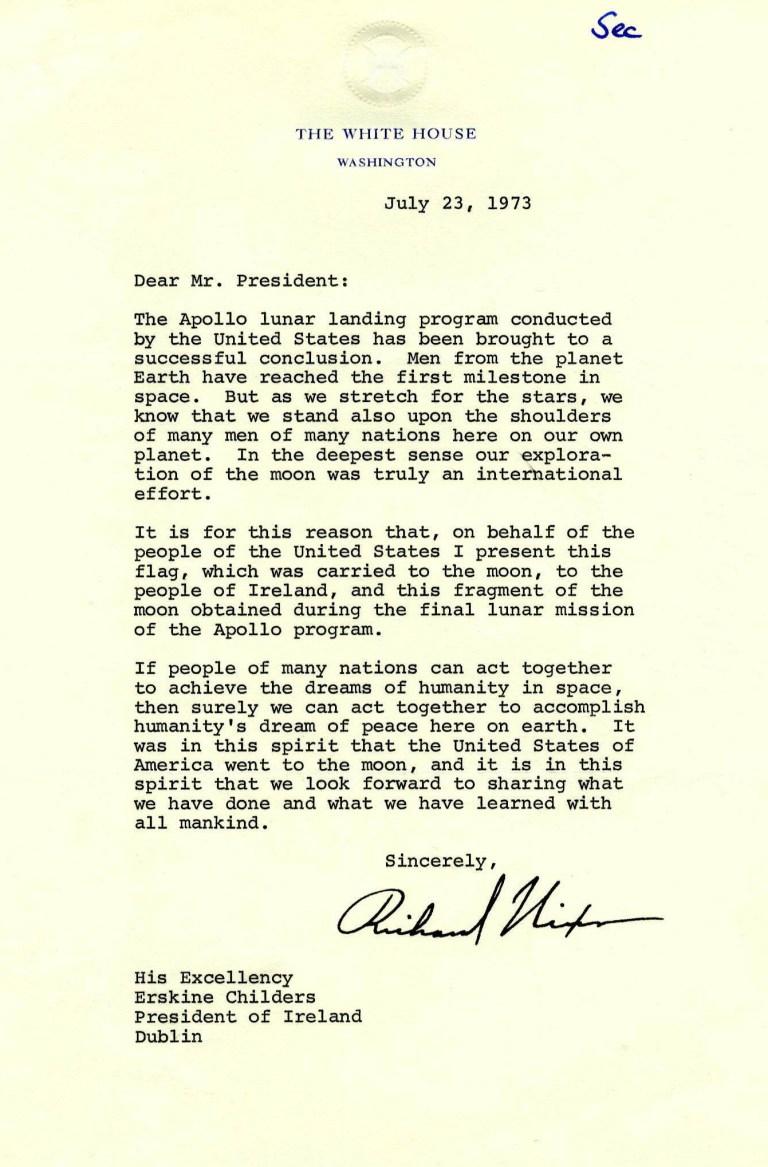

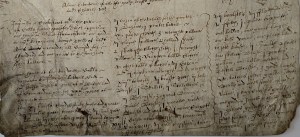

Chancery records can also provide a fleeting glance at the material worlds occupied by residents of early modern Ireland. For example, Houlder v Luttrell, an undated lawsuit between two sisters-in-law over inheritances in rural County Dublin, includes an incredibly detailed itemised list of household items. Maud Luttrell alongside her husband Richard Houlder, claimed to have inherited farms, tenements, and moveable property from her late father, John. John’s widow, Eleanor, had initially taken possession of the properties, which after her death passed to Maud’s brother Walter. When Walter himself died, the property should allegedly have come to Maud by right, but before she could take possession it was appropriate by Mary Luttrell, probably Walter’s widow. The list of disputed property, pictured below, includes an array of household items – napkins, pillows, pots, pans, and candlesticks – along with some luxuries like gold rings, a “big gilt cross”, and “tatches [buckles] silver gilt, with pearls and other stones of good value”. The Luttrells, it is clear, were farmers of some means, and it is not surprising that Maud went to such efforts to claim possession of the disputed property.

The VOICES Project aims to shed light on these remarkable stories and many more. By making high-quality images and transcriptions available online, it hopes to engage a wider audience and inspire further research into Ireland’s rich legal heritage.

To see high quality images along with complete transcriptions of the stories of Margaret Ní Dhonnchadha,the Lady of Lackagh, and the warring Luttrell sisters – please visit the VRTI website